W.K.’s Life up Until the Manor

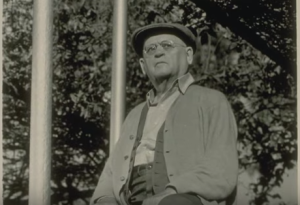

Born on April 7th in 1860 to farmer-turned-broom-maker John Preston Kellogg and his wife Anne Janette Kellogg, Will Keith spent most of his childhood in Battle Creek, Michigan. W.K.’s parents were Seventh Day Adventists in a time when the religion was reaching its peak in Battle Creek. They lived a simple life based on their religious beliefs; a vegetarian diet, no coffee, tea, spices, tobacco, or alcohol. Fresh air, exercise, and pure water were thought to promote clean, healthy lives. W.K. was believed to be a poor student and rather dimwitted in his youth; later, it was discovered that he was nearsighted and merely couldn’t see the blackboard at the schoolhouse. Though he was told he would never amount to anything, W.K. Kellogg would revolutionize the food industry. He dropped out of school at 14 to become a broom salesman for his father, and quickly learned valuable skills regarding business and management. As he grew older, he was sent to Texas for a time where he was placed in a management position that kept him at work for long hours. He came back to Michigan a year later and married his boyhood sweetheart, Ella Davis, and they had five children of which three survived to adulthood. While W.K. worked hard to support his family, Ella’s health deteriorated rapidly and irreversibly. This caused him great strain and only facilitated his lengthy work hours, which often stretched far into the night. He believed that he would “never be a wealthy man,” but never gave up, determined to keep his family afloat.

Born on April 7th in 1860 to farmer-turned-broom-maker John Preston Kellogg and his wife Anne Janette Kellogg, Will Keith spent most of his childhood in Battle Creek, Michigan. W.K.’s parents were Seventh Day Adventists in a time when the religion was reaching its peak in Battle Creek. They lived a simple life based on their religious beliefs; a vegetarian diet, no coffee, tea, spices, tobacco, or alcohol. Fresh air, exercise, and pure water were thought to promote clean, healthy lives. W.K. was believed to be a poor student and rather dimwitted in his youth; later, it was discovered that he was nearsighted and merely couldn’t see the blackboard at the schoolhouse. Though he was told he would never amount to anything, W.K. Kellogg would revolutionize the food industry. He dropped out of school at 14 to become a broom salesman for his father, and quickly learned valuable skills regarding business and management. As he grew older, he was sent to Texas for a time where he was placed in a management position that kept him at work for long hours. He came back to Michigan a year later and married his boyhood sweetheart, Ella Davis, and they had five children of which three survived to adulthood. While W.K. worked hard to support his family, Ella’s health deteriorated rapidly and irreversibly. This caused him great strain and only facilitated his lengthy work hours, which often stretched far into the night. He believed that he would “never be a wealthy man,” but never gave up, determined to keep his family afloat.

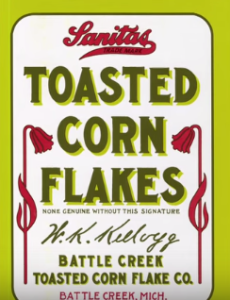

The ideals of living put forth by the Seventh Day Adventist religion had a profound impact on the Kellogg children, most notably Will Keith and his older brother, John Harvey. As the physician-in-chief of the Battle Creek Sanitarium, John Harvey, molded it into a world-famous health spa in order for others to experience the joys of healthy living. The expertise that W.K. learned during his time at the Texas broom factory came in handy when his brother employed him at the Sanitarium in 1880, after he had completed his schooling at Parson’s Business College in Kalamazoo. Contrary to his boyhood teachers’ opinions, W.K. proved to be a clever, dedicated and hardworking student, finishing a degree that should have taken a year in only three months. He worked at the Sanitarium for 21 years performing tasks ranging from developing and testing new healthy products to managing business operations. The Sanitarium, which quickly became a renowned health spa that attracted the world’s elite, was a sanctuary of Adventist ideals and practices. The invention of the toasted corn flake, Kellogg’s signature cereal, would not have been possible without the influence of Seventh Day Adventist philosophy. In an effort to create a healthy substitute for bread, the Kellogg brothers accidentally created the wheat flake in 1894, a happy coincidence that paved the way for the creation of the corn flake. This invention would eventually lead to the founding of the Kellogg Company.

The corn flake ultimately became a fissure between the brothers as they had philosophical differences in regards to its production, causing W.K. to leave the Sanitarium. At the age of 46, W.K. started his own cereal company in 1906, originally called the Toasted Corn Flake Company of Battle Creek. He sold his new cereal product under the name of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes. John Harvey took issue with this and sued his brother for the use of their last name. It was a long and bitter legal battle that drove the brothers apart, and once W.K. won the right to use their last name in the 1920s, the brothers never spoke again. W.K. then changed the name of his company to the Kellogg Company, an institution that continues to thrive today.

The corn flake ultimately became a fissure between the brothers as they had philosophical differences in regards to its production, causing W.K. to leave the Sanitarium. At the age of 46, W.K. started his own cereal company in 1906, originally called the Toasted Corn Flake Company of Battle Creek. He sold his new cereal product under the name of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes. John Harvey took issue with this and sued his brother for the use of their last name. It was a long and bitter legal battle that drove the brothers apart, and once W.K. won the right to use their last name in the 1920s, the brothers never spoke again. W.K. then changed the name of his company to the Kellogg Company, an institution that continues to thrive today.

W.K. spent most of his time growing his company into something worthwhile. Due to W.K.’s foresight and brilliant marketing, the company flourished. He was economical and practical, qualities that stemmed from his humble beginnings and lifelong struggles, but at the same time he was altruistic. He was generous to his employees, providing a nursery, medical and dental clinic, and a dietitian for the children. He also created more work shifts, a ten-acre park to provide work for the unemployed, and a pension fund for veteran employees. His pragmatism and generosity compounded to make W.K. one of the most successful men of the era.

Building Eagle Heights

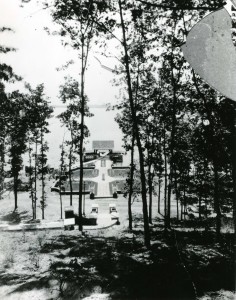

After learning that his assets totaled over one million dollars in the early 1920s, W.K. Kellogg began building his 32 acre Gull Lake estate, Eagle Heights. It would become the summer home of W.K. and his second wife, Dr. Carrie Staines Kellogg. W.K. wanted a historically inspired home that came with all the trappings of an English country estate, as well as being suited particularly for summer use. In 1925 with the help of Grand Rapids architectural firm Benjamin & Benjamin, his vision was brought to paper. Though he did not want to be too far from the Kellogg Company headquarters in Battle Creek, Kellogg needed a place of respite for himself and his family as well as a place of recreation for his valued employees; the Gull Lake site was a perfect choice. At the time, American residential design was an eclectic mix of styles. Architects borrowed motifs and plans freely from the past and combined them with modern building techniques, creating a unique revivalist style to fulfill clients’ aesthetic and practical needs; although W.K., however, had a very particular image in mind. He was a frugal and practical man, and needed some cajoling by his architects to accept their suggestions. Nothing would be done to the estate without first meeting W.K.’s wholehearted approval. Many decisions were carefully considered and then agreed upon by both parties. Major construction on the house and grounds was finished in 1926, with details and landscaping finalized in 1927. The estate included the Carriage House, the Boat House, the Greenhouse, the Caretaker’s Cottage, the Pagoda Garden, Windmill Island, and the Manor House.

After learning that his assets totaled over one million dollars in the early 1920s, W.K. Kellogg began building his 32 acre Gull Lake estate, Eagle Heights. It would become the summer home of W.K. and his second wife, Dr. Carrie Staines Kellogg. W.K. wanted a historically inspired home that came with all the trappings of an English country estate, as well as being suited particularly for summer use. In 1925 with the help of Grand Rapids architectural firm Benjamin & Benjamin, his vision was brought to paper. Though he did not want to be too far from the Kellogg Company headquarters in Battle Creek, Kellogg needed a place of respite for himself and his family as well as a place of recreation for his valued employees; the Gull Lake site was a perfect choice. At the time, American residential design was an eclectic mix of styles. Architects borrowed motifs and plans freely from the past and combined them with modern building techniques, creating a unique revivalist style to fulfill clients’ aesthetic and practical needs; although W.K., however, had a very particular image in mind. He was a frugal and practical man, and needed some cajoling by his architects to accept their suggestions. Nothing would be done to the estate without first meeting W.K.’s wholehearted approval. Many decisions were carefully considered and then agreed upon by both parties. Major construction on the house and grounds was finished in 1926, with details and landscaping finalized in 1927. The estate included the Carriage House, the Boat House, the Greenhouse, the Caretaker’s Cottage, the Pagoda Garden, Windmill Island, and the Manor House.

The Carriage House

The Carriage House was originally planned as a stable before the Kellogg Farm was established. Instead of housing horses and chickens, it became the chauffer’s residence and garage. It had room for seven automobiles, and there were apartments above the garage used by visiting chauffeurs and other domestic staff. The house is a Tudor style that reflects the overarching architectural theme of the estate. Today it houses the outreach program and a conference room used for meetings. The Lakeside Cottage on the west side of the Carriage House offers a beautiful view of Gull Lake and is available for reservation.

The Carriage House was originally planned as a stable before the Kellogg Farm was established. Instead of housing horses and chickens, it became the chauffer’s residence and garage. It had room for seven automobiles, and there were apartments above the garage used by visiting chauffeurs and other domestic staff. The house is a Tudor style that reflects the overarching architectural theme of the estate. Today it houses the outreach program and a conference room used for meetings. The Lakeside Cottage on the west side of the Carriage House offers a beautiful view of Gull Lake and is available for reservation.

The Boat House

The Boat House had two wells that could accommodate 26-foot powerboats. The wells housed W.K.’s sailboat and his Garwood wooden boat when they were not in use. The exterior echoed the architectural theme of the estate as well; it is a two-story, half-timbered structure that sits at the edge of the lake, northwest of the Pagoda. The second floor functioned as a bath with facilities to accommodate 10-12 people when it was still in use by the Kelloggs, a function that speaks to W.K.’s conception of Eagle Heights as not just his summer home, but a place of recreation for all who visited. The Boat House was renovated in 1980 into a lakeside laboratory in order to provide a year-round research space for visiting and resident researchers, including wet and dry laboratories and research cubicles.

Further south of the Boat House is the Pump House, which stored a 50-horse power electric motor that drew water into two 5,000 gallon tanks to irrigate the lawn. W.K.’s interest in innovation ensured the implementation of his irrigation system, a relatively new and expensive invention costing over $100,000. Individual sprinklers, when activated, would rise from the ground and then recede after use, a function only possible with the arrival of electricity to the Gull Lake area. The pump house is still in use today and is used to pump water from the water tower in order to irrigate the lawn.

The Caretaker’s Cottage

During the Kellogg family’s years at Eagle Heights, this was the residence of their gardener, Walter Taylor, and his family. Taylor was the only year-round employee at the estate, residing at Eagle Heights even when the Kelloggs were away. The Cottage stands near the second entrance to the property, set back from the road to offer privacy. It was designed to reflect the general architectural scheme of the estate as well as being a charming residence for a valued employee. It is now used to accommodate visiting guests and is available for reservation.

During the Kellogg family’s years at Eagle Heights, this was the residence of their gardener, Walter Taylor, and his family. Taylor was the only year-round employee at the estate, residing at Eagle Heights even when the Kelloggs were away. The Cottage stands near the second entrance to the property, set back from the road to offer privacy. It was designed to reflect the general architectural scheme of the estate as well as being a charming residence for a valued employee. It is now used to accommodate visiting guests and is available for reservation.

The Greenhouse

Benjamin & Benjamin subscribed to popular architectural opinion that greenhouses were essential to a gentleman’s home as they helped create the illusion of a self-sufficient manor. Within the Kellogg greenhouse grew roses, a grape arbor, citrus fruits, and flowers which supplied the Manor House with fresh bouquets daily. Professor Nutting from Michigan State College “advised and furnished plants responsive to his grafting research” here, a scientific undertaking that W.K. seemed particularly interested in. Many of Professor Nutting’s original tree grafting experiments remain on the estate. Next to the greenhouse sat the orchard, where cherry and apple trees were planted in March 1926. W.K. selected mature trees as he stated, “At my age, you can’t wait for trees to grow.” The greenhouse originally reflected the Tudor theme with decorative wooden trim and a Tudor arch, but was remodeled several times between 1986 and 2006. The Greenhouse is now used for research. It has seven separate growing rooms which are all equipped with the latest technology to ensure optimal growing conditions. The garden house, an extension of the caretaker’s cottage, is home to growth chambers and potting facilities.

Benjamin & Benjamin subscribed to popular architectural opinion that greenhouses were essential to a gentleman’s home as they helped create the illusion of a self-sufficient manor. Within the Kellogg greenhouse grew roses, a grape arbor, citrus fruits, and flowers which supplied the Manor House with fresh bouquets daily. Professor Nutting from Michigan State College “advised and furnished plants responsive to his grafting research” here, a scientific undertaking that W.K. seemed particularly interested in. Many of Professor Nutting’s original tree grafting experiments remain on the estate. Next to the greenhouse sat the orchard, where cherry and apple trees were planted in March 1926. W.K. selected mature trees as he stated, “At my age, you can’t wait for trees to grow.” The greenhouse originally reflected the Tudor theme with decorative wooden trim and a Tudor arch, but was remodeled several times between 1986 and 2006. The Greenhouse is now used for research. It has seven separate growing rooms which are all equipped with the latest technology to ensure optimal growing conditions. The garden house, an extension of the caretaker’s cottage, is home to growth chambers and potting facilities.

Many of the trees and shrubs W.K. planted on the estate are rare species. There are several champion trees on the estate, meaning they are the largest tree of a species. They are measured by trunk circumference, height, and average crown spread, and must be submitted to either the state registry or the National Register of Big Trees, who confirms the size. There are six champion trees on the estate, and all are original to the property.

The 20 acres of trees and shrubs originally planted for beautification of the grounds are open for self-guided walks, and a botanical guide of the estate is available upon request. There are around one hundred species of perennials maintained here, and the flower gardens have been carefully restored to mirror their original splendor. The beautiful grounds and gardens that W.K. conceptualized are meticulously preserved by the KBS Grounds Department, the Rose and Thistle Gardening Club, and many dedicated volunteers.

The Pagoda

Behind the Manor House is a rose garden, and at its edge is a classically inspired stone balustrade leading to a large Ohio sponge-stone and brick stairway that zigzags down to the lake. The Pagoda Garden can be found at the end of this scenic path. W.K. Kellogg reportedly enjoyed this staircase in particular and walked the stairway twice each day for exercise. The Pagoda, a four-posted awning sheltered by a green roof, sits on the lake. With its half-timbered and dog-tooth variant balustrade, it mirrors the aesthetic feel of the rest of the estate. The Pagoda is preceded by a beautiful symmetrically arranged garden complete with sundial, urns, and rose arbors. It is an ideal location to view sunsets on Gull Lake and is used as a landmark by boaters; when the family was in residence, the Pagoda was used as a docking and unloading point for lakeside visitors of the Kelloggs. Today many couples are married at the Pagoda.

Windmill Island

Windmill Island is named for the authentic Dutch windmill that sits on the edge of the southwestern-most part of the estate, a small island that can only be reached by two arched bridges. The windmill is a smock mill, named for the fact that the body looks vaguely like a dress or smock. Only the top of the mill is able to move, which allows the main body some permanence while giving the sails more flexibility in catching wind. Windmills were not only used to saw, press, or mill, but to pump water out of lakes and keep lowlands dry. The Kellogg windmill is actually comprised of two mills, both nearly one hundred years old. The original hailed from Ijlst in the province of Friesland, The Netherlands, but had several faults which Benjamin & Benjamin thought would not meet Kellogg’s expectations. A second mill was bought which originally stood on the east bank of the Palsepoel, a lake near Heeg and Ijlst. It was a farm mill that was used to regulate water from the lake using the Archimedean screw, and later served to regulate the estate’s lagoon. The two mills were shipped to Gull Lake in pieces to avoid taxation and reassembled onsite into one mill in 1927. A small tulip garden laid at the mill’s feet, and the island was often used as a recreational area for W.K.’s grandchildren and his employees. Mythical statues were placed in the lagoon surrounding the island, and there was even a running fountain in the Grotto that may have been connected to the underground water system.

*most information on structures found in W.K. Kellogg and His Gull Lake Home, From Eroded Cornfield to Estate to Biological Station by Linda Oliphant Stanford.

Architecture and Interior

The Kellogg Manor House is a beautiful example of the Tudor Revival Style that was prevalent from 1890 to 1940. The style was generally ranked high in suitability for residences, and fit W.K.’s need for a gentleman’s estate. The Manor House has the typical Tudor half-timbering, oversized fireplaces, and stucco siding, along with steeply pitched roofs and an asymmetrical floorplan. Wood of the finest quality was utilized frequently within the house, an element typical of Tudor homes. The house was made for sensibility and durability, having an undercurrent of success, imbuing the house with tasteful elegance. Much of the interior and design is a quiet display of wealth.

The Kellogg Manor House is a beautiful example of the Tudor Revival Style that was prevalent from 1890 to 1940. The style was generally ranked high in suitability for residences, and fit W.K.’s need for a gentleman’s estate. The Manor House has the typical Tudor half-timbering, oversized fireplaces, and stucco siding, along with steeply pitched roofs and an asymmetrical floorplan. Wood of the finest quality was utilized frequently within the house, an element typical of Tudor homes. The house was made for sensibility and durability, having an undercurrent of success, imbuing the house with tasteful elegance. Much of the interior and design is a quiet display of wealth.

The Manor House sports original Rookwood tile designs, many of which are still being made today. Seven, W.K.’s favorite number, is a recurring theme within the Manor, as he instructed his architects to use it whenever possible. The motif can be found in many rooms in the house, as well as standard heraldic shields and symbols that were typical of Tudor designs. There are many English and Scottish influences within the house, a link back to W.K.’s and Dr. Carrie Staines’ heritage including a Kellogg coat of arms designed by W.K.’s favorite sister, Hester Kellogg. The library boasts a rampant lion design within the plaster back wall, a symbol of courage and strength. At the lion’s feet lies a Bezant, a gold coin symbolizing generosity and prosperity. These small details weave a discreet tale of success and determination, a quiet testament to the life goals W.K. Kellogg fought so hard to achieve.

The craftsmanship within the Manor had to be superb to meet W.K.’s expectations. The intricate rose and thistle design, symbolizing the seventh son and hardship respectively, on the living room ceiling, light fixtures, and wall sconces was created by Frederick C. Ruppel, a well-known sculptor based in Grand Rapids. The elaborate English Gothic oak staircase in the entryway was hand-carved onsite by Lindhout & DeKorne Carving Works over the course of two years. Though most of the original furniture was either given to his children or auctioned off at the time of his death, W.K. Kellogg’s summer home has been carefully preserved and restored. The interior has been meticulously recreated to show its original splendor using saved receipts from Marshall Fields, W.K.’s favorite store.

A legacy of conservation; a commitment to sustainability.

3700 E. Gull Lake Drive

Hickory Corners, MI 49060

(269) 671-2400

conference@kbs.msu.edu